Capital Gains Tax

FinanceCapital Gains Tax; a complex tax that refuses to stay the same, with each government adding its own take on what ‘Simplifying’ looks like [1]

Figure 1, an excerpt from an analysis by the IFS, demonstrating that this isn’t the first acknowledgement of the complexity of Capital Gains Tax. (J.R.King 1985). [2]

Keeping hold of that tradition, the most recent changes came into force on the 6th of April 2024 (and may change again with a new government inbound).

So what are the changes?

- The higher rate for gains on residential property has reduced from 28% to 24%.

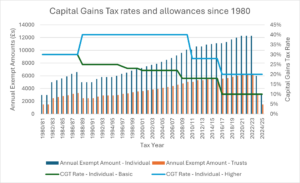

- The Capital Gains Tax allowance [3] has now reached a new low of £3,000 for individuals after trending higher in recent years (reaching the lofty highs of £12,300 in 2020/21 – 2022/23).

A reduction in tax rates is usually well received for fairly obvious reasons (even if this only benefits higher/additional rate property owners), but a reduction in tax allowances is seen more negatively as this applies to all tiers of earners.

By lowering the allowance available the proportion of realised gains that becomes taxable increases. For example, the sale of an asset outside of a tax wrapper (such as funds held in a General Investment Account) has a much higher likelihood of incurring a tax liability now than in previous years, with investors previously not paying capital gains tax now caught by this change.

In previous tax years, the larger allowances available enabled tax planning to happen relatively easily and ad-hoc sales during rebalancing of portfolios wouldn’t move the dial much either. Based on this information, my clients have been quite happy to spread sales over a few tax-years to pay minimal capital gains tax. With the allowances now so small, a portfolio rebalance (where shares are bought and sold to maintain the chosen investment strategy) for large accounts with multiple holdings is more likely to now incur capital gains in excess of the allowance, and the same tax planning to avoid CGT would now take much longer to achieve the same work previously.

For my more ‘tax-led’ clients, the mere thought of paying capital gains tax amounts to heresy.

But is paying CGT really as bad as people think?

Hear me out:

Historically, CGT has been rated at 30%, income tax rates, 18/40%, 18/28%, before settling on todays rates of 10/20%. This is the lowest they have ever been making it a very cost-effective time to realise gains.

We cannot predict the future decisions of the next government, but we can make decisions based on what we know now, and what has happened before. Given how unpredictable these changes have been, why not make profitable hay whilst the cheap tax sun shines?

- Capital Gains Tax is a sign of having made good financial decisions

You have invested wisely, maybe a little too wisely. Your assets have grown and you are going to have to pay some tax to reap your reward, and only on the growth not the capital. It is a clear indication that things have been going in the right direction for your finances. If that doesn’t quite sit, would you rather instead see losses and definitely have no tax liability?

- Dividend allowances are also much smaller, and Savings allowances are relatively smaller following rate rises, meaning more income tax by not tackling built up gains.

Dividend allowances have dropped to £500 for the 2024/25 [6] before tax is charged, and interest rate increases now mean that income tax on savings and bonds are now highly likely. By holding onto an asset that earns these income streams, rather than paying Capital Gains tax at 10% or 20%, income tax is instead being charged at 20/40/45% on interest and 8.75/33.75/39.35% on dividends.

- Potential Inheritance Tax implications

Current legislation has that the base cost of an asset is rebased to the value of the asset on the date of your death. For example, a shareholding of £250,000 with a base cost of £100,000 implies an unrealised gain of £150,000. On death, the shareholdings base cost is revalued to the value on date of death, from £100,000 to £250,000, so now there is no gain thereby removing any potential gains you’d built up in your lifetime [7]. Great news!

However, by not tackling these gains in your lifetime and incurring gains at 10% for basic rate taxpayers or 20% for higher and additional rate taxpayers on only the gains in your lifetime, you’ve instead potentially passed on an Inheritance Tax bill of 40% on the entire holding to your descendants. Not so good news!

For example, Brian holds £300,000 of company shares with a £150,000 unrealised gain. Selling the entire holding to diversify elsewhere or gift away would have incurred at most £30,000 of tax (20% of £150,000). Should Brian have done nothing, there would be no CGT but Brian has an estate in excess of his Nil Rate Bands which means this holding will likely be liable to IHT. This means that his executors will have to pay £120,000 (40% of £300,000) due to inheritance tax.

Sometimes trying to avoid paying tax ends up leading to more being paid (even if you are not necessarily around to see it!).